Hello, student researcher!

Have you ever found yourself in the middle of a research project, feeling torn between using a survey to get hard numbers and conducting interviews to gather personal stories? You’re not alone. This is a classic dilemma in the world of research. For a long time, researchers were often pushed to choose one path: either the statistical world of quantitative research or the narrative-driven world of qualitative research.

But what if you didn’t have to choose? What if you could use the power of both?

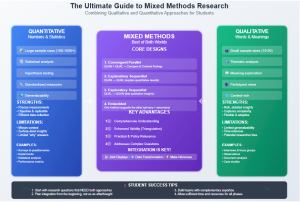

This is the core idea behind Mixed Methods Research. It’s an innovative, powerful approach where you systematically collect, analyze, and integrate both quantitative and qualitative data in a single study. Think of it as a research superpower. Instead of seeing these two methodologies as competing philosophies, mixed methods sees them as complementary tools that, when used together, can create a far more comprehensive, nuanced, and robust understanding of your research problem.

In this guide, we’ll dive deep into what mixed methods is, why you should consider using it, and most importantly, how you can do it successfully in your own academic projects.

Why Use Mixed Methods? The Power of Combining Data

Mixed methods research isn’t just about combining data for the sake of it. It’s a purposeful strategy designed to achieve goals that a single method cannot. Here are the three most compelling reasons to use this approach.

The Ultimate Research Guide for High School Students Sample

Triangulation: Building a More Robust Argument

Triangulation is the process of using multiple methods or data sources to confirm and cross-validate your findings. Imagine you’re a detective trying to solve a case. You wouldn’t rely on just one witness’s testimony; you’d look for fingerprints, check alibis, and talk to other witnesses. Each piece of evidence strengthens the overall case.

In research, triangulation works the same way. If your quantitative data (e.g., a survey showing that 75% of students feel stressed before exams) and your qualitative data (e.g., interviews where students describe the specific pressures and feelings of stress) point to the same conclusion, your findings are significantly more credible and defensible. You are building a more robust, “airtight” argument for your thesis. If the data from both sources align, you can be much more confident in your conclusions.

Completeness: Answering the “What” and the “Why”

One of the biggest limitations of a single-method study is that it often provides only a partial picture.

- Quantitative research excels at answering “what,” “how much,” and “how often.” It can tell you that there is a significant correlation between hours of study and exam scores.

- Qualitative research excels at answering “why” and “how.” It can tell you why students with more study hours feel more prepared and how they organize their time and materials.

By using mixed methods, you can get the best of both. Your survey can identify the relationship between study hours and grades, and your interviews can explain the underlying reasons for that relationship. This combination provides a complete, holistic understanding of the phenomenon you are studying.

Illumination: Bringing Your Findings to Life

Numbers and statistics can be powerful, but they can sometimes feel cold and impersonal. A pie chart showing that 40% of students use a specific study app is informative, but it doesn’t tell you anything about their actual experience.

This is where qualitative data shines. You can use it to illuminate your quantitative findings by providing vivid, humanizing details. A direct quote from a student interview—”I love the app’s flashcard feature; it’s the only thing that helps me remember complex formulas”—makes the quantitative finding more relatable and impactful. It transforms your data from a mere statistic into a tangible human experience, making your research more engaging and memorable for your readers.

The Main Mixed Methods Designs: Choosing Your Research Path

The “mixed” in mixed methods research isn’t a random blend. It’s a deliberate choice based on your research goals. The way you combine the methods is called your research design. There are four common designs, and choosing the right one is the most critical decision you’ll make.

1. The Convergent Parallel Design: When Both Sides are Equal

This is the most straightforward design. You collect quantitative and qualitative data at the same time but analyze them separately and independently. After both sets of analyses are complete, you “converge” the results by comparing them to see if they corroborate, diverge, or add to each other.

- When to use it: When you want to use both types of data to get different, but complementary, perspectives on a single phenomenon. It’s excellent for triangulation.

- How it works: You simultaneously run a survey on students’ opinions about the university’s career services (quantitative) and conduct a series of focus groups with a different group of students to explore their experiences with those same services (qualitative). Then, you compare the statistical findings from the survey with the key themes that emerged from the focus groups.

2. The Explanatory Sequential Design: Numbers First, Stories Second

In this two-stage process, you start with the quantitative phase. After you collect and analyze the numbers, you use those results to inform a second, qualitative phase. The qualitative data is used specifically to help explain, elaborate on, or explore unexpected findings from the quantitative data.

- When to use it: This is the ideal design when you want to use qualitative data to help explain puzzling or surprising quantitative results.

- How it works: You conduct a campus-wide survey that reveals a statistically significant but unexpected finding: students who live off-campus report higher levels of social satisfaction than those living in dorms. To understand why, you then conduct follow-up qualitative interviews with a select group of off-campus and on-campus students to explore their social experiences, friendships, and community-building efforts.

3. The Exploratory Sequential Design: Stories First, Numbers Second

This design is the reverse of the explanatory model. You begin with the qualitative phase to explore a topic where there is little existing research. The insights and themes you discover from this initial phase are then used to inform and build a second, quantitative phase. This is often used to develop a new survey instrument or to test a hypothesis that emerged from your initial qualitative findings.

- When to use it: When you are exploring a new or under-researched topic and need to understand the key issues before you can measure them.

- How it works: You are researching the impact of a new campus mental health program. You first conduct in-depth interviews with a few participants to understand their experiences, feelings, and the specific terms they use to describe the program. Based on the common themes that emerge (e.g., “accessibility,” “stigma,” “wait times”), you then create a large-scale survey with specific questions to measure these exact concepts across the entire student body.

4. The Embedded Design: Supporting Your Main Study

In this design, one method is your primary method (either quantitative or qualitative), and the other is a secondary, or “embedded,” method. The embedded data is collected to provide supplemental or supportive information to the main study. It’s less about equal integration and more about enrichment.

- When to use it: When your research is primarily one type, but you feel that adding a small amount of the other would provide crucial context or a deeper understanding of a specific part of your study.

- How it works: You are conducting a large-scale quantitative experiment on a new teaching method. Your primary goal is to measure its effect on grades. However, you also include a small qualitative component where you interview a handful of students about their personal feelings and engagement with the new method. The interview data provides a richer context for interpreting the grade-based statistics, but the core of your study remains the quantitative experiment.

A Practical Guide to Conducting Your Own Mixed Methods Study

Ready to try it yourself? Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you plan and execute your mixed methods research project.

Step 1: Formulating a Mixed Methods Research Question

This is your foundation. Your research question must be designed to be answered by both types of data, not just one. It should clearly indicate that you will be collecting both quantitative and qualitative information.

- Poor Question (Single Method): “Do students find the online writing center helpful?” (This can be answered with a simple survey).

- Better Question (Single Method): “What are students’ experiences using the online writing center?” (This is best answered with interviews).

- Excellent Question (Mixed Methods): “What is the relationship between students’ use of the online writing center (quantitative) and their reported feelings of academic confidence (qualitative)?”

Notice how the excellent question explicitly mentions both types of data, setting you up perfectly for a mixed methods approach.

Step 2: Selecting the Right Research Design

Based on your mixed methods question, you need to decide which of the four designs (Convergent, Explanatory, Exploratory, or Embedded) best fits your goals. Ask yourself:

- Do I need to explain an unexpected finding? (Explanatory)

- Am I building a new survey or scale? (Exploratory)

- Do I want to get two different, but equal, perspectives on the same topic? (Convergent)

- Am I running a big study and just want a little extra context? (Embedded)

Choosing your design early on will save you a lot of time and potential confusion later.

Step 3: Data Collection and Analysis (A Two-Part Process)

This is where the real work begins. You will be conducting two distinct, but connected, research efforts.

- Quantitative Data Collection: This can be surveys, existing institutional data (like grades or attendance records), or experimental results. Make sure your survey questions are clear, and your sample size is appropriate for the kind of statistical analysis you plan to do.

- Qualitative Data Collection: This typically involves interviews, focus groups, or open-ended questions. Your goal here is to gather rich, descriptive information. Make sure your interview questions are open-ended and allow participants to share their stories freely.

- Quantitative Data Analysis: You’ll use statistical tools (like descriptive statistics, correlations, or t-tests) to find patterns and relationships in your numbers.

- Qualitative Data Analysis: You’ll use coding, thematic analysis, or narrative analysis to identify key themes and patterns in your textual data.

Step 4: The Crucial Step: Integrating Your Findings

This is what truly makes your study “mixed methods.” Simply presenting a quantitative section and a qualitative section is not enough. You must actively connect and compare them.

- Connecting: You might use a finding from your quantitative data (e.g., a high correlation) and then use a quote from your qualitative data to illustrate and explain it.

- Comparing: You can directly compare the themes from your qualitative analysis to the statistical results of your quantitative analysis to see if they align.

- Synthesizing: You can combine the results from both methods to create a new, more complete understanding that neither method could have provided on its own.

Your integration should be a central part of your results and discussion sections, where you explicitly show how each dataset informs and enriches the other.

Navigating the Challenges of Mixed Methods

While powerful, mixed methods research is not without its hurdles. Being aware of these challenges ahead of time will help you prepare.

The Integration Puzzle: Making the Data Talk

The biggest challenge is often integrating the data effectively. It’s easy to analyze the quantitative and qualitative data separately and then just place them side-by-side in your paper. This is what’s known as “two-monolith” research, and it misses the whole point. You must plan for integration from the very beginning. Will you use qualitative data to explain your quantitative findings? Will you compare the results directly? Will you merge the datasets at a single point? Your design choice should dictate the integration strategy.

Time, Resources, and Scope Management

Let’s be honest: conducting a mixed methods study takes more time and effort than a single-method study. You’re essentially running two research projects at once. For a student with a limited timeline, this can be a significant constraint. You might need to adjust the scope of your project. For example, instead of a campus-wide survey, you might do a smaller one. Instead of 20 interviews, you might do 5-10. Managing your scope is essential for a successful, timely project.

Ethical Considerations in Mixed Methods Research

Combining methods also brings up unique ethical considerations.

- Confidentiality: It’s vital to ensure that your quantitative data (which might be tied to student IDs or names) cannot be linked to the personal, often sensitive, stories you gather in your qualitative interviews.

- Informed Consent: Your informed consent form must clearly state that you are collecting both types of data and explain how you will protect confidentiality for both.

- Participant Selection: In designs like the explanatory sequential, you’ll be selecting interview participants based on their survey responses. You must be transparent about this process and ensure it’s done fairly and without bias.

A Case Study: A Student’s Mixed Methods Project in Action

Let’s imagine a student named Maya who is researching the impact of a university’s new “Wellness Hub.”

- Research Question: “How does student engagement with the Wellness Hub (quantitative) relate to their perceptions of their overall well-being (qualitative)?”

- Design Choice: Maya chooses an Explanatory Sequential Design. She wants to see if the Hub is being used and then understand why it is or isn’t making a difference in students’ lives.

- Phase 1 (Quantitative): Maya first creates a survey that is sent to all students. The survey asks questions about their frequency of visits to the Wellness Hub, which services they use, and for a self-rated score of their general well-being.

- Finding: The survey data reveals a surprising result: students who visit the Hub most frequently do not report a significantly higher well-being score than those who never visit.

- Phase 2 (Qualitative): Puzzled by this, Maya moves to the qualitative phase. She selects a small group of students who reported using the Hub frequently but still had low well-being scores. She conducts in-depth interviews with them.

- Finding: The interviews reveal a consistent theme: these students are often visiting the Hub out of desperation or because they are in a state of high stress, so their visit is a symptom of a problem, not a cure. They report feeling overwhelmed and unable to fully utilize the services.

- Integration: In her final paper, Maya integrates the two findings. She explains that while the Hub is being used (the quantitative finding), the qualitative data provides the crucial context, showing that the high usage might be a sign of a larger, systemic problem with student mental health and that the Hub’s current services might not be equipped to fully address the severity of the issues faced by its most frequent users. She is able to make a much stronger, more nuanced argument than if she had only looked at the numbers.

Conclusion: Your Research, Supercharged

Mixed methods research is a challenging but incredibly rewarding approach that will push you to think more creatively and critically about your research questions. It is no longer a niche method; it’s a powerful tool that is being embraced across countless academic disciplines because of its ability to produce comprehensive, credible, and impactful results.

By learning to combine the statistical rigor of quantitative data with the rich, human insights of qualitative data, you will be producing work that is not only methodologically sound but also deeply meaningful. You will move beyond answering simple questions to tackling complex, real-world problems.

So, the next time you’re faced with that choice between numbers and stories, remember you can have both. Your research—and your understanding of the world—will be all the better for it.